Note - from June 24th 2009, this blog has migrated from Blogger to a self-hosted version. Click here to go straight there.

A couple of questions were raised this week - the answers are moderately convoluted, so I'll have a crack at them, but these will be more in the "stream of consciousness" paradigm rather than a tightly reasoned explanation.

The first query concerned the property market (which I take to mean residential property in a major capital city; regional property markets are vcery much a creature unto themselves). The other was about my comments on the "Free Trade Agreement" with the United States. I'll get to the FTA when I've gotten good and liquored up so I an really get a rant on... for now I'll have a crack at the...

Property Market.

I've been bearish on property for a couple of years now - so far it's been the wrong view to have if you're the sort of person who likes to speculate in highly illiquid assets using massive leverage. I'm not that sort of person, so holding a bearish property view hasn't hurt me at all.

The property market in major urban centres in Australia (anyplace bigger than Albury) continues to defy investment logic; most of this problem is concentrated in major metropolitan areas, and in particular Sydney and Melbourne.

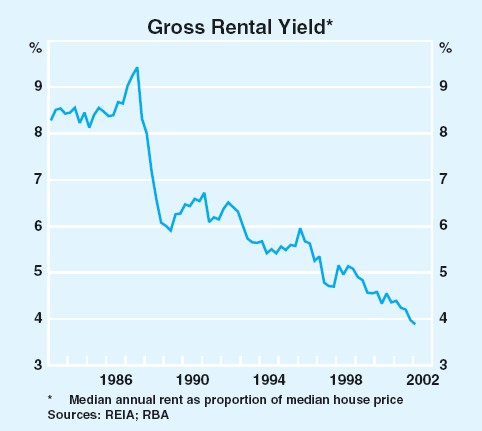

At present the average gross rental yield is only slightly higher than 10-year bond yields. That leaves precious little room for the maintenance and ongoing expenses associated with property investment.

Debt service as a proportion of income has seldom been higher, and yet interest rates have seldom been lower.

In other words, everyone expects to make their gains via capital appreciation; it's the "Greater Fool Theory" from the stock market, but with a much higher degree of leverage.

The "heady" days of buying apartments off the plan have passed, much to the chagrin of those who have been absolutely roasted by doing so. Likewise, we are getting past the ludicrous proposition that you can slap some paint on a structurally-unsound property, scatter some cushions and rented furniture around, and add $40k to the price: I said a couple of years back that when there are two TV shows about that sort of malarkey, we are near a top in the property market. There ended up being three such shows, and now there are only two again... and the auction results recently have been pretty miserable (but of course when there is only one vendor bid on auction day, we are told by the Lovely Joanna that someone buys it after the camera stopped rolling... pshaw).

There are a couple of historical reasons why people hear from their parents that "you can't go wrong with bricks and mortar". This has affected the investment expectaitons of a huge crop of 30-somethings who don't see property investment for wha it is - as I said above it is a massively leveraged bet on a highly illiquid asset.

The "property is a no-brainer" hypothesis is really a no-brainer... people who believe it have no brains. It is a fallacy based on a historically-anomalous period - the huge burst of inflation and expansion of monetary aggregates in the 1970s.

The result has biased investment decisions in favour of property for almost a generation. This has led to the situation in which the "normal" gross yield (income only) on property barely exceeds bond yields - something in the 5-7% range is considered better-than-acceptable, and the latest data that I could find showed something considerably lower than that (see below for a chart of just how far yields have fallen- it only covers until 2002). Bear in mind that the rental yield on property is similar to the PE on stocks (it is closer - conceptually - to the dividend yield on stocks, but ignores maintenance, rates and other upkeep costs).

Would you buy a stock with a PE of 25, when every man and his dog were tripping over themselves to buy the same stock - on 90% margin?

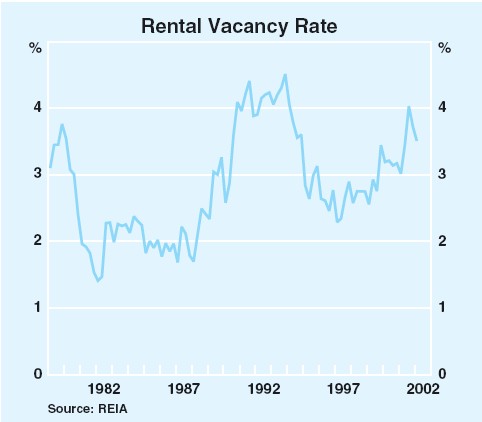

Bear in mind also, that that gross rental yield is not adjsuted for "idle periods". The "expectation" of the gross rental yield, is equal to the occupancy rate times the gross rental yield. Occupancy rates are declining (i.e., vacancy rates are increasing - see below).

Think for a minute as to why the current crop of 60-somethings - who view stockmarket investment as highly risky - might think highly of the property market.

When they bought their first properties - usually the house in which they intended to raise a family - they were able to finance the purchase with a fixed 25-year mortgage at rates at or below 5%. That was in the mid-to-late 60's; employment was relatively plentiful and debt service ratios were manageable.

During the 1970s there was a period of inflation such as the world had not seen before (except in highly concentrated situations, e.g., Germany during the Weimar Republic, France during John Law). Price inflation topped 10% on average over the 1970's - and assets inflated faster than prices.

So by the end of the 1970s the current crop of 60-somethings - who were barely 40 at this stage - were sitting on an asset that had doubled or tripled since they bought it. Since most people don't think hard enough about real returns, they thought they had struck it rich; also, because wages tend to rise with prices, the fixed mortgage payments became trivial in relation to inflation-augmented wages.

So the primary experience was of rising asset prices with an attendant debt obligation that became much more manageable with the passing of relatively few years.

If you're convinced that you've found a money machine with attributes like that, it will appear to make sense to go and get hold of as many copies of the machine as you can afford - hence the "second property" craze which continues to this day.

Second-property mortgages came into the "average" property investor's sights in the 80's; interest rates were high, but "everybody" knew that over time, inflation made the fixed repayments shrink relative to rental income from the property (which grew with inflation).

There was also the discovery of "negative gearing", and the capital-gains tax benefits from property ownership.

Add to that a 22-year bull market in bonds and the opportunity to refinance second-property mortgages at the decreasing rates which resulted, and you have a recipe for a slow-simmering mania.

The end-game for these sorts of events is never pretty.

There were also people who financed property investment when interest rates were much, much higher; of the order of 18% for a standard mortgage. The terrific thing for those people was that they purchased when prices were low (because of the damping effect of high interest rates on demand). Still, enough people found themselves in a "negative equity" situation at the end of the 1980's to have cause a real problem for banks; many of them behaved irrationally - holding on to an asset that was worth less than they owed on it, hoping that time and inflation would get them out of the hole.

History shows us that this is what happened; a lot of people with negative equity were "saved" by the subseuqent bull market in bonds and the ability to refinance mortgages with more advatageous interest rates.

That sort of logic - "I was showing a big loss, but now I'm showing a profit, so I'm a genius" - reminds me of dumb stock traders, who will buy a share at $1, see it fall to $0.05, then spruik their "win" when it claws its way back to $1.01 (if it ever does). Far better to ditch the thing at 80c (or when it approaches a sensible measure of "fair value") and buy it back lower. I know... that's hard to do with a house considering the illiquid nature of the market, but it's still sensible to watch valuation ratios for property and exit the market when they get too rich.

The present landscape sees the entire property market being buoyed by low interest rates. Because rates are so low and competition in mortgage markets is so aggressive, mortgage finance is being extended on some ludicrous terms. We have all seen the ads that tell us that we can live in such-and-so a new development with no money down ... and the developer will even give us back the $7 thousand government homebuyers grant.

The laxity of lending standards means that there is a larger pool of "cashed up" (really, they're debted up) potential buyers. People who are earning roughly average weekly earnings (which is now $50k for a man working full-time) are out borrowing half a bar ($500k) for a 3 bedroom terrace. And people give themselves a little cheer when they're the highest bidder on a property, even if they exceed their budget.

I've heard some people (property investors, HIA people and "Real Estate Institute" types, mostly) who tout the fact that inner-city housing is in naturally-restricted supply and so with growing demand prices will naturally rise.

Where is this "demographic shift" coming from, in a country with slowing population growth? People moving from the country to the city don't have the budget to drive property price up - and besides the urbanisation of this country has been happening at a more-or-less steady pace since Federation.

It's not caused by us breeding faster, either - age cohorts are smaller as we move away from the Baby Boomers.

It's not the "tidal wave of woggoes"... Migrants generally arrive without much capital - and besides, without them population would be contracting.

So the "migration to the resticted inner-city" hypothesis is another "no brainer"... believe it, and you've got no brain.

The thing which id driving real estate prices - still - is just a shift in the tolerance for debt and leverage. It's all driven by notions that have their roots in a lucky coincidence - widespread new access to mortgage markets in the 60's couple with a massive burst of inflation in the 70's.